The practice of distillation dates back to antiquity: as early as the 1st century AD, Alexandrian physicians used the alembic to obtain hydrosols and essential oils from medicinal plants. In the Middle Ages, thanks to Arab alchemists, the technique was refined and spread throughout Europe for the production of spirit drinks. From the medieval “aqua vitae” to the prized Italian grappas, distillation became both art and science, rooted in the local traditions of each country.

The Dangers of Distillation

Before delving into the technique, it is essential to remember the main risks and how they vary depending on whether you are distilling grappa (from pomace) or brandy (from wine):

- Methanol Toxicity

- Grappa: pomace is particularly rich in pectins, which release a higher amount of methanol during distillation. Therefore, the “heads” must be discarded with absolute rigor.

- Brandy: already-fermented wine contains fewer pectic precursors, so the methanol content in the heads is lower but still non-negligible.

- High Ethanol Concentration

- In both cases, the “heart” of the distillate typically reaches 60–75% ABV, a highly flammable level that can cause acute intoxication if consumed in excess.

- Vapor Explosion Risk

- Alcohol vapors, denser and more flammable above 50% ABV, can accumulate in unventilated spaces, posing an explosion hazard both during heating (boiler) and cooling (condenser).

- Mechanical Hazard

- Grappa: solids and foam from pomace can clog columns and pipes, causing flashbacks or localized overheating.

- Brandy: the cleaner liquid reduces this risk, but it is still good practice to filter the wine thoroughly before distillation.

- Legal Aspects

- In Italy, amateur distillation without an ADM license is prohibited for both grappa and brandy: all activities require specific authorizations.

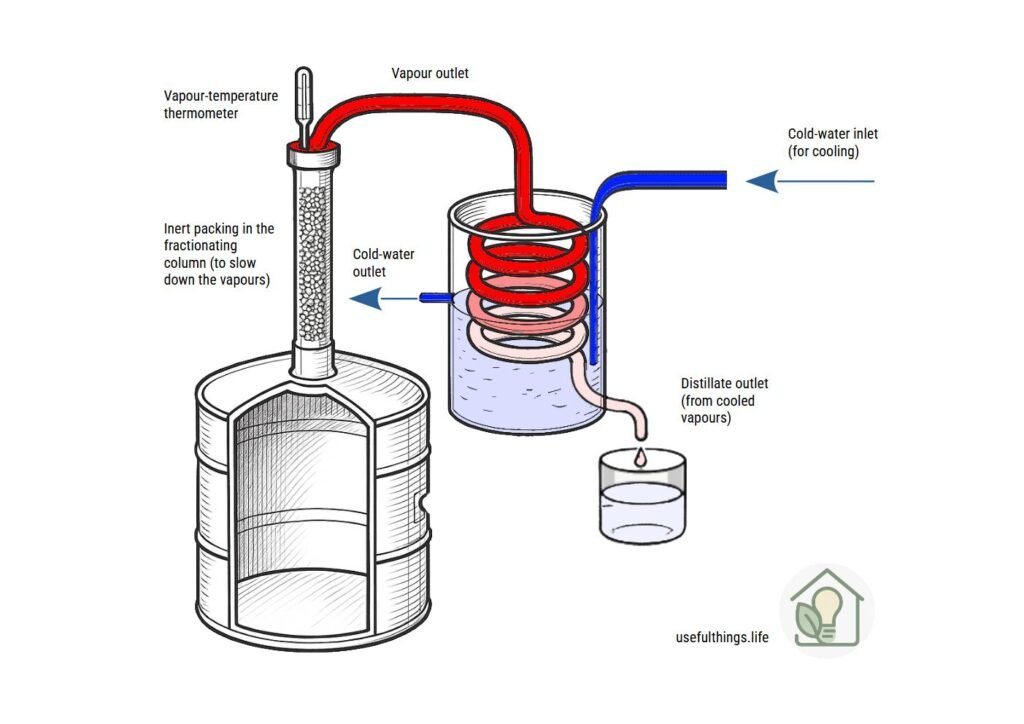

Construction of the Still

A still consists of three main parts: the boiler, the fractionating column (or neck), and the condenser.

- Boiler

- Material: copper or food-grade stainless steel.

- Shape: wide base to promote even evaporation.

- Fractionating Column

- Importance: it is the “heart” of the still, where vapor and refluxing liquid interact.

- Function: increases alcohol purity by separating more volatile components (methanol, acetaldehyde) from less volatile ones.

- Types:

- Plate column: perforated plates that allow multiple condensation-evaporation cycles, yielding a “cleaner” distillate.

- Packed column: filled with inert packing rings or material, which increase surface area for vapor-liquid contact.

- Condenser

- A coil immersed in a cooling bath (cold water).

- Must provide rapid heat exchange to convert vapor back into liquid.

The fractionating column (also known as the deflegmation, reflux, or rectification column) is the crucial component of the entire setup: it not only ensures a high degree of distillate purity but—thanks to the addition of inert packing or other vapor-slowing systems—allows for extremely precise monitoring of vapor temperature. This precision is essential for making a clean cut between the heads, heart, and tails, thereby achieving a perfect fraction separation.

To build an effective column, simply use a steel tube filled with glass beads, rings, or food-grade metal sponge.

Specific rings for packing a deflegmation column Ceramic Raschig Rings - Anelli in ceramica

To prevent the packing material from falling into the boiler, insert a stainless steel mesh or filter at the base.

A suitable boiler can be an oil drum made of stainless steel; a reasonable size is around 50 liters as shown in the photo.

The condenser can be a vessel into which you insert the coil at one end and create a bottom outlet. You should also include an overflow for cooling water, and the inlet tube must reach the bottom of the container. Place a frozen water bottle in the middle to maintain low temperatures.

Necessary Materials

- Complete still (copper or stainless steel), with safety valves.

- High-precision thermometer (0–100 °C) at the top of the column.

Find the digital thermometer here Digital thermometer - Termometro digitale

- Controllable heat source: electric hotplate or water bath, NEVER an open flame.

- Collection vessels in glass or stainless steel.

- Seals and tubing resistant to heat and alcohol.

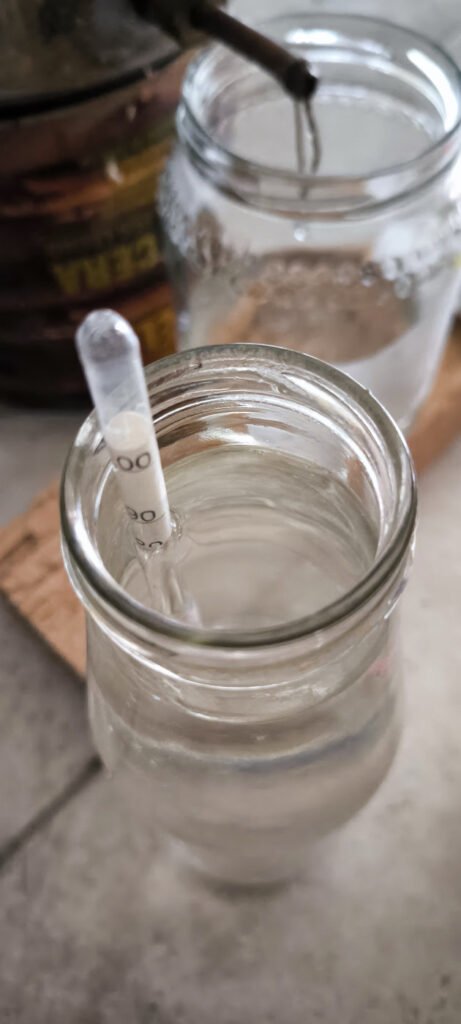

- Measuring instruments: hydrometer or alcoholmeter to measure alcohol content.

Find alcohol content measurement tools here Alchol tester

- Safety equipment: gloves, protective goggles, dry powder fire extinguisher.

Distillation Stages

- Loading

- Fill the boiler with already-fermented wine (for brandy) or pomace (for grappa).

- Do not exceed ¾ of the volume to avoid overflow.

- Heating and Stabilization

- Heat slowly to 78–80 °C, monitoring temperature stability.

By setting the flame extremely low, as the liquids that evaporate at a specific temperature vaporize and exit, the temperature automatically rises.

- Heat slowly to 78–80 °C, monitoring temperature stability.

- Fraction Cutting

- Heads: first fractions (about 1–3% of the total) contain methanol, acetaldehyde, and other volatile compounds. Discard completely.

- Heart: middle, most prized fraction.

- For brandy: about 60–70% of the distillate; strength 60–75% ABV.

- For grappa: about 50–65%; strength 55–65% ABV.

- Tails: last fractions (20–30%), contain fusel oils and heavier compounds; can be re-distilled or discarded.

- Graduated Collection

- Use an alcoholmeter or distillation table to precisely separate fractions.

- Keep separate discard containers for heads and tails to avoid contaminating the heart.

- Reduction and Aging

- If needed, add distilled water to bring the spirit to the desired strength (e.g., 40% ABV).

- Allow to age in neutral or wooden containers to enhance aroma and roundness.

Let us add further detail on the heads, heart, and tails, as these are the fundamental parts when distilling.

Heads

The “heads” are the first fraction to emerge from the still: they contain volatile components with boiling points below that of ethanol (78.4 °C), such as ethyl acetate and methanol. Although these compounds contribute some aromas, they are largely undesirable: methanol is toxic and an excess of these light compounds compromises the cleanliness and quality of the spirit. Thus, heads are always discarded or sent for further rectification.

Heart

Also called the “body,” the heart contains the most prized part of the distillate: here concentrate the compounds with boiling points between 78.4 °C and 100 °C, and in particular the highest proportion of pure ethanol. It is in this phase that the finest and most characteristic aromas are found, which is why the heart is considered the fraction of greatest quality and typicity.

Tails

The “tails” are the final portion of the distillate and begin to emerge when the temperature exceeds 90–100 °C. They contain higher-boiling components, such as fusel oils and other unpleasant compounds, which weigh down and spoil the organoleptic profile. Tails are therefore separated and can, if properly treated, be re-distilled in a second run.

Conclusion

Here you can find a simple flame-ready distiller.

Although rooted in ancient traditions, distillation remains a complex and potentially dangerous chemical process. From the design of the still to the cutting of fractions, each step requires attention, precision, and compliance with regulations. By following best practices—ventilation, certified equipment, accurate cuts of heads and tails—you can achieve high-quality brandies and grappas safely.

Leave a Reply